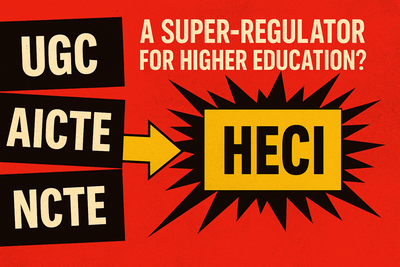

India’s higher education system—spread across 1,113 universities and 43,796 colleges, according to the AISHE 2021–22—is heading for what may be its most sweeping institutional overhaul since the university system was nationalised. The government has dusted off its reformist rhetoric to dismantle a decades-old triad of regulatory overlords: the University Grants Commission (UGC), the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), and the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE). In their place, it proposes a singular body—the Higher Education Commission of India (HECI)—tasked with doing everything the other three were supposed to do, but better, faster, and without the administrative clumsiness.This wasn’t a bolt from the blue. Policymakers had flagged the chaos earlier too. The National Knowledge Commission (2005–2009) warned of regulatory fragmentation and called for the dismantling of the UGC-AICTE-NCTE triad. It was followed by the Yash Pal Committee Report (2009), which made an even more urgent pitch: “Multiplicity of regulatory agencies leads to lack of coordination and policy incoherence.” Neither report was fully acted upon. Successive governments chose to tinker, not transform. Then again in 2018, under the Ministry of Human Resource Development (now renamed Ministry of Education), policymakers pitched HECI as a leaner and allegedly more autonomous alternative to the UGC. The concept matured in the National Education Policy 2020, which went a step further—recommending the merger of all three regulators into a single apex commission. One ring to rule them all.At first glance, it sounds like a long-overdue bureaucratic detox. But beneath the calls for efficiency and streamlining lies a deeper story—one of centralised control, collapsed specialisation, and the quiet possibility of academic overreach. Because whenever a government promises to fix complexity with centralisation, it’s not just structure that gets rewritten. The soul of the system changes too.So the questions write themselves: Why now? Why one regulator? And who watches the one who watches everyone else?

A legacy of silos and silence

Historically, India’s post-independence higher education system relied on a sector-specific regulatory structure, with different bodies overseeing different streams of education. The University Grants Commission (UGC), established in 1956, was responsible for regulating universities and general higher education institutions. It handled tasks such as funding allocations, curriculum development, and maintaining academic standards across disciplines like arts, science, and commerce.The All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), originally set up in 1945 and granted statutory status in 1987, was tasked with overseeing technical and professional education, including engineering, management, architecture, pharmacy, and hotel management. Meanwhile, the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE), established in 1995, regulated teacher education programmes, setting norms, granting approvals, and monitoring institutions offering degrees such as B.Ed. and M.Ed.Each of these regulators operated in isolation, with distinct mandates and regulatory frameworks—a model that made sense when disciplines were neatly boxed, institutions were fewer, and regulation meant inspection rather than innovation. But the 21st-century Indian campus is anything but boxed. A single institution may today offer a B.Tech in AI, a B.Ed in science pedagogy, and a minor in ethics and literature—and find itself caught in a three-way tug-of-war between regulatory bodies who seldom talk to each other. The result? Not oversight, but overhead. Not accountability, but administrative fatigue.

Where did things go wrong?

On paper, the tripartite regulatory model—UGC for universities, AICTE for technical education, and NCTE for teacher training—was neat, logical, and compartmentalised. But by the late 2000s, the system began to unravel under the weight of its own silos. India’s higher education was evolving, institutions were expanding, disciplines were blending—and the regulators stayed frozen in time.

Overlapping jurisdictions, colliding mandates

The first cracks appeared when colleges started breaking out of their traditional academic ghettos. A private university might now offer an integrated B.Tech in Data Science with a liberal arts minor. An institute of education might pair a B.Ed with environmental studies or STEM modules. Sounds progressive? Yes. But for the regulators, it triggered a turf war.In such cases, the institution had to seek separate approvals from UGC, AICTE, and NCTE—each with its own forms, deadlines, inspections, and (often contradictory) compliance requirements. What followed was:

- Duplication of compliance: One course. Three sets of paperwork. Dozens of inspections.

- Conflicting mandates: What AICTE allowed in the name of innovation, UGC might reject as non-conforming.

- Funding delays: Institutions caught in the crossfire often lost out on timely grants and accreditations.

In short, the multi-regulator setup became less about quality assurance and more about bureaucratic endurance.

Fragmented quality control

While regulatory overlaps created confusion, quality control turned into a blindfolded relay race.All of the three bodies—UGC, AICTE, and NCTE—ran their own accreditation show. They used different metrics, had separate assessor pools, and often reached conflicting conclusions about the same institution. There was:

- No unified quality benchmark: What counted as “excellent” for UGC might be sub-par by AICTE standards.

- Interdisciplinary blind spots: A university with strong arts and tech programmes might ace UGC review but stumble with AICTE red tape.

- Opaque student experience: For learners navigating cross-disciplinary degrees, the regulatory alphabet soup offered little clarity and even less consistency.

At the heart of it, there was no single dashboard, no composite score, no common yardstick for institutional performance.

Inefficient governance and regulatory fatigue

Beyond structural flaws, each of the three regulators carried its own baggage.

- UGC, burdened with both funding and monitoring powers, often found itself in a conflicted dual role—allocating grants while also policing quality. This raised perennial questions about fairness, favouritism, and political influence.

- AICTE, though credited with standardising technical education, developed a reputation for rigidity and red tape. While industries moved toward emerging tech, AICTE’s curriculum norms were often several updates behind.

- NCTE, perhaps the weakest of the three, became infamous for its inability to curb the proliferation of dubious teacher training colleges, especially in smaller towns. The result: thousands of “recognised” institutes with questionable teaching capacity and negligible placements.

What emerged was a governance model where no single body could be held fully accountable, and all three seemed to operate in parallel bureaucracies, rarely in sync, and often in conflict.

Enter HECI: What it promises to fix

Unlike its predecessors, HECI isn’t a one-department show. It’s structured around four autonomous verticals, each focused on a distinct function.

NHERC: Regulation without redundancy

The National Higher Education Regulatory Council (NHERC) will be the front-facing gatekeeper—handling approvals, compliance, and the creation of academic norms. Its job is to bring clarity to the tangled web of regulations by becoming the single-window authority for all higher education institutions (except medical and legal). This means no more running from UGC to AICTE to NCTE for the same degree programme.

NAC: Accreditation that speaks one language

Accreditation duties will shift to the National Accreditation Council (NAC). Unlike today’s fractured system where different bodies use different metrics, NAC is meant to apply a uniform, outcome-based framework for quality assurance. One council, one scale, one yardstick—for all institutions, regardless of discipline.

HEGC: Funding that rewards merit

The Higher Education Grants Council (HEGC) will take over funding responsibilities from UGC—but with a twist. Instead of discretionary allocations and opaque grants, HEGC is expected to link funding to performance. Think academic outcomes, research impact, graduate employability—not just political connections or compliance checkboxes.

GEC: Curriculum that reflects the present

Lastly, the General Education Council (GEC) will steer the academic ship. It will define learning outcomes, curricular frameworks, and pedagogical standards across institutions. Its aim is to modernise what’s taught and how, making sure Indian students aren’t studying for yesterday’s job market.

What’s the real pitch?

At its core, HECI is being sold as a regulatory reset—streamlined, centralised, and outcomes-driven, replacing clutter with clarity.

One regulator, less bureaucracy

Perhaps the biggest headline is administrative simplicity. HECI’s integrated model means institutions will no longer bounce between three regulatory bodies. Compliance processes are expected to be leaner, faster, and less redundant.

One standard, clearer quality

With NAC at the helm, the patchwork of quality assessments will be replaced with a single, transparent accreditation system. Students and parents may finally get a clear, comparable picture of institutional performance.

One body, more accountability

Instead of UGC blaming AICTE or NCTE washing its hands off quality lapses, HECI creates a unified command. With verticals working in tandem, there’s less room for regulatory blame games and more space for system-wide accountability.

From control to outcomes

HECI is also being pitched as a philosophical shift—from an input-focused, micromanaging bureaucracy to an outcome-driven regulator. In theory, it will care more about results than rules, creating room for greater institutional autonomy.

Money follows merit

Under HEGC, public funding may finally move toward performance-linked models—rewarding institutions that innovate, publish, and place, rather than simply comply. The goal is to incentivise quality, not paperwork.

But HECI isn’t a silver bullet: The risks and red flags

For all its ambition, HECI carries risks that policymakers cannot afford to ignore:

Excessive centralisation

- Critics fear HECI could become a super-regulator with too much power concentrated at the Centre.

- If not insulated from political influence, it could be used to enforce ideological conformity across campuses.

Loss of domain expertise

- AICTE and NCTE, for all their flaws, brought specialised understanding of engineering and teacher education.

- Merging everything under one roof may dilute this expertise unless HECI’s verticals are empowered with expert teams.

Academic autonomy at risk

- NEP 2020 advocates “light but tight” regulation. But if HECI dictates curriculum frameworks, funding norms, and accreditation—all at once—autonomy could become a buzzword, not a reality.

Bureaucratic bottlenecks

- A monolithic body may end up replicating the red tape of its predecessors.

- Institutional grievances could get lost in the system if not backed by robust grievance redressal mechanisms.

So, will HECI deliver?

The idea of HECI, on its own, is not the problem. In fact, it reads like a long-overdue footnote to a history of regulatory disarray—one that spans decades of overlapping jurisdictions, incoherent policy mandates, and watchdogs too exhausted to bark. As a concept, it echoes earlier reformist impulses—from the National Knowledge Commission’s call for consolidation to the Yash Pal Committee’s plea for coherence—both of which gathered dust in government archives while institutional entropy thrived.But as any student of policy will tell you, ideas don’t govern—structures do, and structures are only as good as those who operate them. If executed with clarity, autonomy, and genuine insulation from political puppeteering, HECI could finally offer India what the UK has in the Office for Students, or Australia in TEQSA: a regulator that enforces standards without stifling thought, and funds institutions without measuring their worth in compliance checklists.But done badly—and that’s not a hypothetical in Indian policy history—it could become yet another monolith with a new acronym and the same old reflexes: delay, dilution, and disinterest in outcomes. New gatekeepers, same revolving doors.As the draft bill inches closer to reality, the real question is not just what HECI abolishes, but what it institutionalises in its place. Because a unified regulator should never become a uniform regulator. And in a democracy that aspires to knowledge leadership, simplification must never come at the cost of dissent, complexity, or intellectual autonomy.TOI Education is on WhatsApp now. Follow us here.