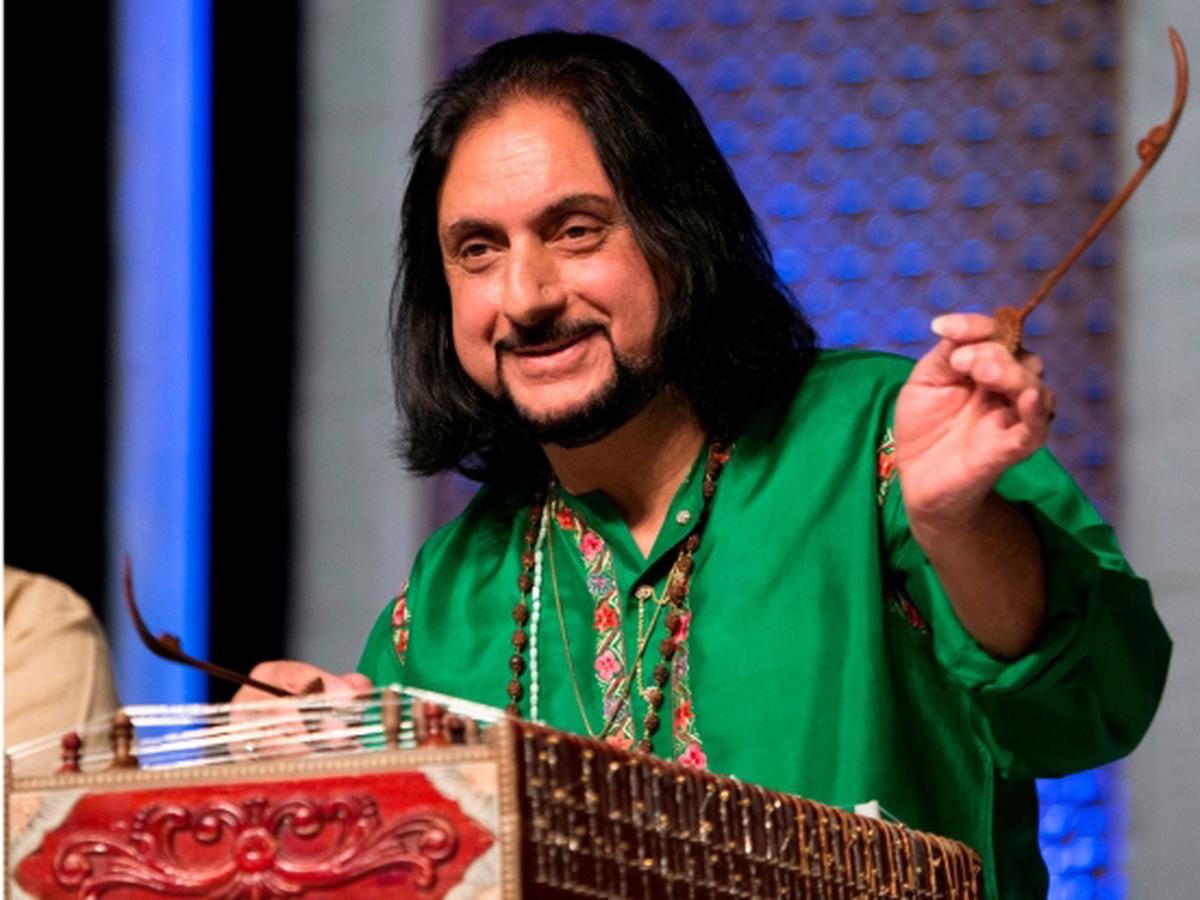

Abhay Rustum Sopori.

| Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

Watching Abhay Rustum Sopori play raag Bhagwati, his own creation, on the santoor at a recent concert during the Pandit Kshitpal Mallick Music festival in Delhi, one thought about the instrument’s long journey from the hills to the plains. Thanks to the efforts of two musicians from Jammu and Kashmir – Pt. Shiv Kumar Sharma and Pt. Bhajan Sopori, the santoor shed its ‘folk’ tag to become part of the classical music world. Both exponents brought in necessary changes to enable the santoor’s 100 strings to reproduce raag, taal and swar.

Abhay’s santoor has been modified too. Its deep meends make it sound like a surbahar while the bow-like movement of its wires is reminiscent of the violin. Though traditionalists may see it as tampering with its distinct sound, it does enhance the aural experience.

Apart from Bhagwati, Abhay has four more raags to his credit. All of them have a characteristic shakal (look). For a new raag to be acknowledged, the creator should be able to easily interpret it, and its grammar must be distinctly visible. A key phrase in Bhagwati is ‘pa dh ni sa’.

Pt. Bhajan Sopori brought in necessary changes to enable santoor to reproduce raag, taal and swar.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

His father Bhajan Sopori, who hailed from the sufiana gharana of santoor, also created raags. Abhay seems to have imbibed his father’s compositional skills.

At the concert, after a brief aalap, Abhay played the jor section, accompanied by Rishi Shankar Upadhyay on the pakhawaj. The playing style was not the traditional ‘taar paran’ pakhawaj accompaniment, which involves playing the same intricate stroke work on both instruments, instead the artistes got into a creative mode and arrived on the beat together in a glorious culmination. In the Ek taal composition that followed, Mithilesh Jha gave him sangat on the tabla. Abhay’s ‘barhat’ follows a system, it is not merely building on a tune.

During a chat after the concert, Abhay shared that his father had ingrained in him the importance of this systematic approach. He was told to analyse what he played, how he played, and why he played.

Talking about his family’s bond with the instrument, Abhay shared that his grandfather, in the 1930s, increased the bridges on the santoor from 25 to 28. This was done to add more wires to play more notes. Abhay’s father further improvised its sound by adding a few more bridges and wires. Abhay, during his experiments with the instrument, introduced the flat ‘Jawari’ bridges. His santoor, made by Devi from Benaras, has 43 bridges and one can play three octaves on it. With ‘meends’, notes can be played up to five-and-a-half octaves. Though the strings remain 100, Abhay’s modified santoor has additional ‘chikaari’ and ‘tarab’ strings while the ‘tumba’ helps in balancing the instrument and acts as a resonator.

According to Abhay, these modifications are not planned. “They happen organically since you are constantly connected to the music.”

Abhay also uses broader mallets (kalam) with greater sound sustenance and volume control. The striking technique involves four movements – finger, wrist, elbow and shoulder, which lend depth and diversity to the tonal quality.

With increased scope and range, Abhay Sopori wishes to take the santoor to newer musical settings.

Published – October 18, 2024 02:57 pm IST