Time for us is a constant, relentlessly moving forward. The ticking of a clock on the wall, the steady march of seconds on a digital display — they’re such familiar concepts that we rarely stop to consider the physical processes that underpin them.

At its heart, any clock is a physical system that evolves in a predictable way, creating a record of the passage of time. Scientists are now exploring what timekeeping means at the smallest possible scale, in the quantum realm, and their findings could hone how physicists think about the role of measurement in timekeeping.

A study published in Physical Review Letters on November 14 by researchers from Austria, Italy, Ireland, Switzerland, and the UK delved into this world by building and analysing a quantum clock. The researchers reported a surprising insight in their paper: that the energy cost of simply looking at a clock to read the time could exceed the energy required to make the clock tick in the first place. This discovery, if it’s borne out in more research, could have important implications — for the future of ultra-precise timekeeping with devices like optical clocks as well as for the development of quantum technologies and scientists’ grasp of the laws that govern the universe at its most fundamental.

Shattered glass

Understanding the researchers’ motivation demands first appreciating an important concept from physics called entropy. It’s often colloquially described as a measure of disorder. In formal terms, entropy is linked to the second law of thermodynamics, which states that in an isolated system, entropy always tends to increase. This relentless increase is what gives time its arrow, its direction of evolution.

The clockwork of a basic quartz wristwatch. Bottom right: quartz crystal oscillator, left: button cell watch battery, top right: oscillator counter, digital frequency divider and driver for the stepping motor (under black epoxy), top left: the coil of the stepper motor that powers the watch hands.

| Photo Credit:

Garitzko/Public domain

For example, a shattered pane of glass has more entropy than one that’s intact, and we will never see the shards spontaneously reassemble. It’s this principle of irreversible processes that allows a clock to create a lasting record of the past, distinguishing it from the future. For all practical purposes, a clock’s counter always increases, which aligns with our everyday experience that clocks always tick ‘forward’.

At the macroscopic scale of our everyday lives, this is straightforward. The swinging of a pendulum or the vibrations of a quartz crystal are processes that consume energy and produce entropy, driving the clock’s hands forward. But in the quantum world, things are not so simple. Quantum systems are governed by probabilities and can exhibit strange behaviours. The amount of entropy produced by quantum processes is generally orders of magnitude lower than in classical processes. This can lead to situations where, due to random fluctuations, a quantum clock might briefly tick ‘backward’.

This presents a conceptual tension. A clock, by its very definition, must be an irreversible device that reliably distinguishes past from future. How can a quantum system, with its inherent randomness and potential for backward steps, function as a true clock?

Ticks of a quantum clock

The authors of the new study hypothesised that the solution lies not just in the clock’s internal mechanism, or its clockwork, but in the process of measurement itself. They proposed that the act of extracting information from the quantum system — i.e. observing the ticks to create a classical, readable record — must also produce entropy. This ‘cost of observation’ could be the missing piece that enforces the forward flow of time, even when the quantum clockwork itself is at a standstill, the team figured.

The motivation for the new study was to experimentally test this idea. The team aimed to build a quantum clock where they could separately measure the entropy produced by the internal clockwork and the entropy produced by the measurement apparatus. This would allow the researchers to directly compare these two costs and determine which one is more fundamental to the process of timekeeping at the quantum scale. Such an experiment would be the first to explore the interplay between the entropy produced by a microscopic clockwork and its macroscopic measurement apparatus.

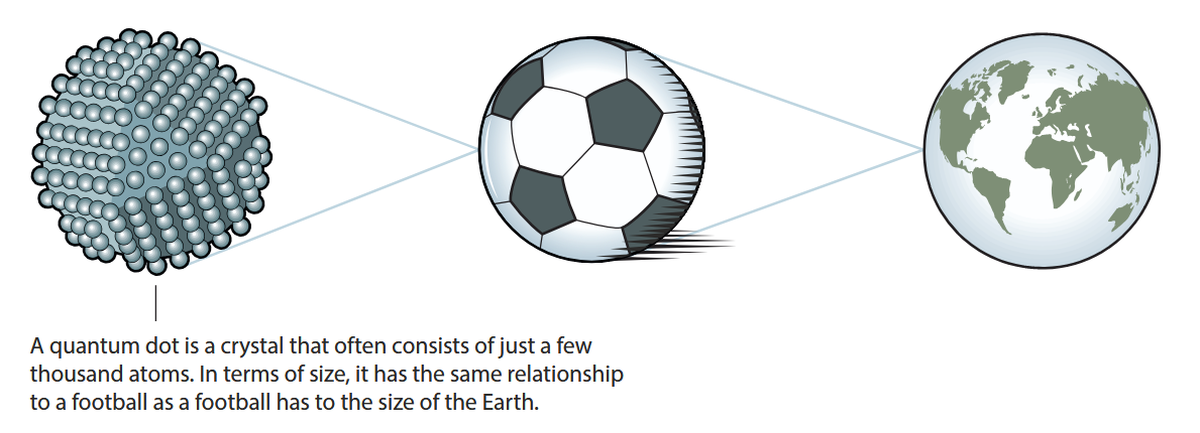

To realise their quantum clock, the scientists used a device called a double quantum dot (DQD). Imagine two minuscule human-made islands in a semiconductor material, so small that they can hold only one extra electron at a time. These are quantum dots. (Their inventors were rewarded with the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 2023.)

The researchers used the movement of single electrons across a pair of quantum dots – whose size is explained here – to denote the tick of a clock.

| Photo Credit:

Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

By applying precise voltages, the researchers could control the movement of a single electron, causing it to tunnel from a source onto the first dot, then to the second dot, and finally off to a drain. (The demonstration of quantum tunnelling in a large circuit won the Nobel Prize for physics in 2025.) This sequential movement of an electron constituted a single tick of the team’s clock.

Reading the time

The state of the DQD could be in one of three configurations: no excess electron on either dot (which we’ll call state 0), an electron on the left dot (state L) or an electron on the right dot (state R). A forward tick is a full cycle, for instance from states 0 to L to R⟩and back to 0, as the electron traversed the dots.

To ‘read’ the time, the researchers needed to know which state the DQD was in at any given moment. They accomplished this using a nearby charge sensor — which was another quantum dot whose electrical properties were sensitive to the location of the electron in the DQD. By measuring the current flowing through this sensor, they could deduce whether the DQD was in state 0, L or R. This measurement process, however, wasn’t free: it required energy and therefore produced entropy.

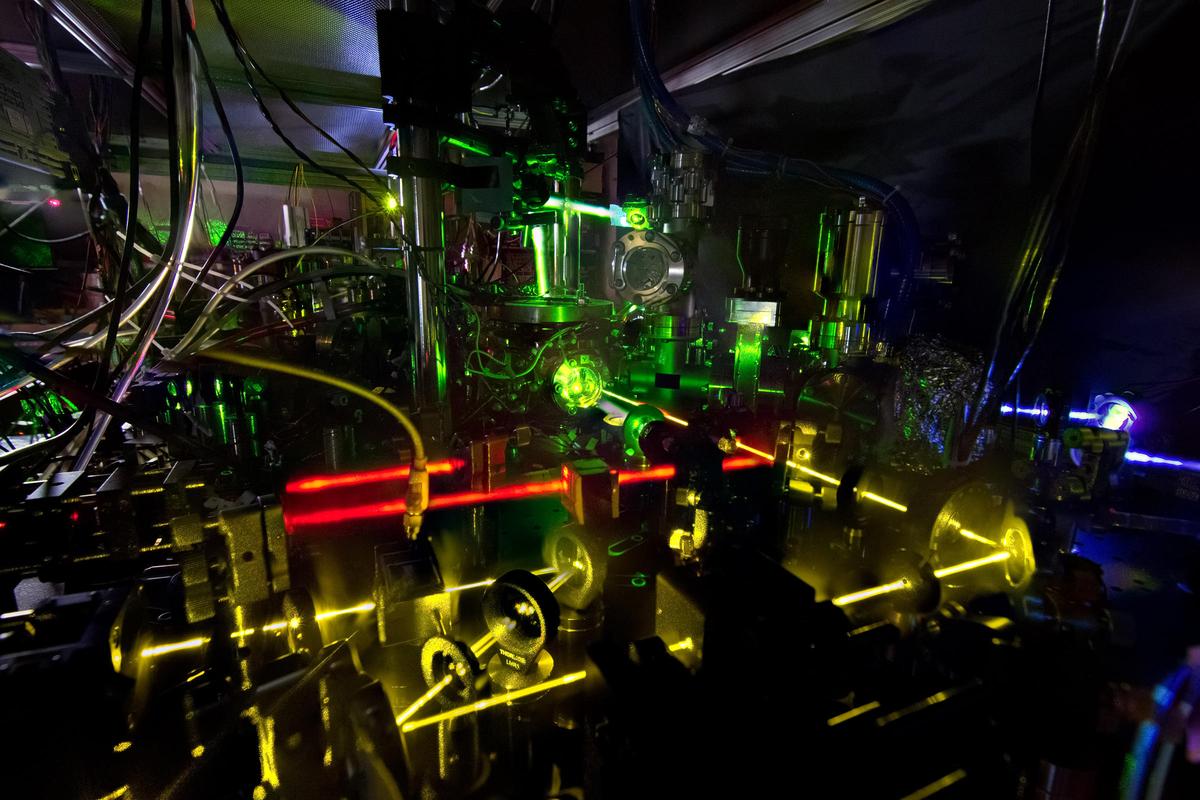

The team used two different methods to read the sensor: a direct-current (DC) measurement and a more sophisticated radio-frequency (RF) reflectometry technique. This allowed them to vary and precisely measure the power dissipated, and thus the entropy generated, by the act of observation itself. By simultaneously controlling the voltage across the DQD, which dictated the energy dissipated by the clock’s tick, they could independently study the thermodynamic costs of both the clockwork and ‘reading the time’.

Source of irreversibility

The results of the experiment seemed striking. The researchers first examined the relationship between the clock’s precision and the entropy produced by its internal workings, i.e. the DQD. As predicted by thermodynamic principles, they found that a more precise clock — one with more regular and forward-moving ticks — required more entropy. When the DQD was brought to equilibrium, where forward and backward ticks were equally likely, the clockwork produced no net entropy, and its ability to record the passage of time vanished.

However, the researchers’ more remarkable claim emerged when they analysed the entropy cost of the measurement process. They found that the entropic cost of extracting the classical ticks from the quantum clock was the dominant factor by an astonishing nine orders of magnitude. In other words, the energy dissipated to simply find out what time it was dwarfed the energy needed to make the clock tick, by a factor of a billion.

The team also showed that the measurement process could effectively retrieve the information that makes the device a clock. This was because even when the internal clockwork was at equilibrium, i.e. producing no entropy, the act of continuously monitoring the DQD created an irreversible, classical record of its state changes. This record, generated at a significant entropic cost by the measurement device, allowed the researchers to estimate the passage of time.

Sure, in your house as well, reading time from the device on the wall gives you the time information that also makes the device’s identity a ‘clock’. But here’s what’s unique about the quantum clock: the team interpreted their results as evidence that in the DQD clock, the dominant source of irreversibility needed for timekeeping comes from the act of observation, not from the clockwork itself!

These findings also reinforce those reported by a different group in 2023: that ‘reading the clock’ is an invasive process in quantum timekeeping that can’t be taken for granted. The new study also complicates and deepens the understanding of precision reported in the 2023 study by showing that the effect of measurement isn’t monolithic. Instead of ‘reading the clock more often is better’, the new study seems to report a more complex reality: the relationship between measurement strength and precision depends on the clockwork.

Physics of timekeeping

The study’s implications could be far-reaching, touching on fundamental physics, metrology (the science of measurement), and the future of quantum computing. Perhaps foremost, it suggests that the oft-ignored interaction between a quantum system and its classical measurement device isn’t just a technical detail: it’s a central part of the physics involved. The entropy produced by the amplification and measurement of a clock’s ticks is the most important and fundamental thermodynamic cost of timekeeping at the quantum scale.

At least one implication is potentially practical: current atomic clocks — which are some of the most accurate timekeeping devices in existence — could be improved by designing more thermodynamically efficient measurement systems. That is, by minimising the entropy cost of observation, it may be possible to create clocks that are even more precise.

A clock, by its very definition, must be an irreversible device that reliably distinguishes past from future. Atomic clocks, like the ytterbium lattice clock shown here, can make that distinction with extreme precision.

| Photo Credit:

NIST

The principles the new study has explored are also not limited to clocks. Any quantum computer will depend on being able to precisely control and measure quantum states. Understanding the thermodynamic costs associated with extracting information from a quantum system is crucial for engineers to design efficient and scalable quantum machines. The authors’ approach feeds into a broader line of work on the energy cost of quantum measurements, which may eventually inform how engineers design quantum computers.

Finally, some physicists interpret such results as suggesting that the clear, unidirectional flow of time that we experience may not be solely a property of the microscopic world itself. Instead, it could be a feature that emerges anew from the process of extracting and recording information on a macroscopic scale.

In the classical proverb, a watched pot never boils. In these quantum clock experiments, the pot certainly boils, but turning its bubbles into a reliable stopwatch turns out to be costly.