When the Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority (PFRDA) released its consultation paper on enhancing the National Pension System (NPS), it did something remarkable. For the first time, it asked not just how much Indians should save for retirement but how those savings can translate into a stable monthly pension.

For two decades, the NPS has built a solid base of long-term savers. What it hasn’t yet offered is predictability after retirement. Retirees still ask questions like ‘How much pension will I get’, ‘Will it last my lifetime’, or ‘Will it keep up with inflation’. The new consultation paper takes a major step toward answering these questions.

New pension ideas

The paper proposes three withdrawal options. My research focuses on the first two, because they are immediately executable and lend themselves to empirical testing. The rigorous evaluation of these proposals has been detailed in my working paper at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_ id=5601211 (bit.ly/4nnoj8W). This column presents the key findings from that study.

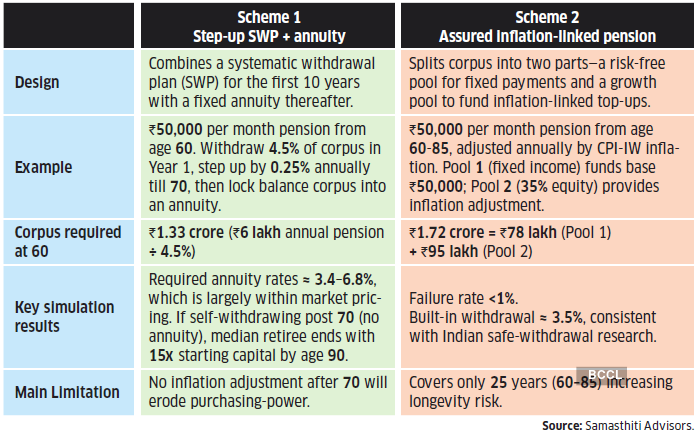

Pension Scheme 1 combines a systematic withdrawal plan (SWP) in the early years with an annuity later. A retiree begins by withdrawing 4.5 per cent of their corpus at age 60, then increases the withdrawal rate by 0.25 per cent every year for the first ten years. At age 70, the retiree locks into a fixed lifetime annuity. The plan assumes a balanced portfolio with 35 per cent in equity.

Pension Scheme 2 goes one step further. It splits the retirement corpus into two pools. One part invested safely to fund a fixed pension (Pool 1) and the other part invested in a balanced portfolio of equity and fixed income (Pool 2) to top up the pension each year with inflation.

Putting the ideas to the test

To see how these schemes would behave in real-world markets, we ran thousands of simulations using 25 years of Indian data on equity, bond and inflation returns. The results were encouraging.

For Scheme 1, the key risk for a 60-year-old retiree is the annuity rate that will be offered to them when they are 70 years old. Our analysis suggests that retirees would need an annuity yield of roughly 3-6 per cent to keep receiving the same pension after age 70. This is comfortably within current market pricing.

Even more interestingly, if retirees skip the annuity and continue self-withdrawals, the median ending wealth by age 90 is nearly 15 times their starting capital. This not only illustrates how equity exposure can boost retirement wealth but is also a hint on the feasibility of annuity products around this withdrawal scheme.

For Scheme 2, which targets an inflationlinked pension, the results are even stronger. The simulated failure rate, which is the chance of the corpus running out before age 85, was under 1 per cent. The Scheme 2 design works well because the risk-free Pool 1 delivers a steady base income, while the growth-oriented Pool 2 funds inflation adjustments. The built-in withdrawal rate of about 3.5 per cent aligns closely with our earlier research on India’s sustainable withdrawal rates, confirming that the model is both sound and realistic.

What these results mean

In plain terms, both schemes work, and they work with parameters that are practical for Indian conditions. Scheme 1 offers retirees simplicity and choice, while Scheme 2 offers predictability and inflation protection. Together, they can transform the NPS from a pure savings plan into a real pension system.

Of course, there are limitations as well. Scheme 1’s post-70 annuity does not rise with inflation, so purchasing power will slowly erode. Scheme 2, by fixing a 25-year payout horizon, limits coverage for those who live beyond 85. But these are manageable design issues, not structural flaws.

A defining policy moment

For years, India’s pension conversation has revolved around accumulation. We have spent endless energy on how to get people to save more. The harder part, which is converting those savings into a reliable lifetime income, has received far less attention.

PFRDA’s consultation paper changes that focus. It introduces clear, testable blueprints that bridge this gap. If adopted and fine-tuned, these schemes could mark the beginning of a true social-security architecture for India.

The author is co-founder, samasthiti advisors