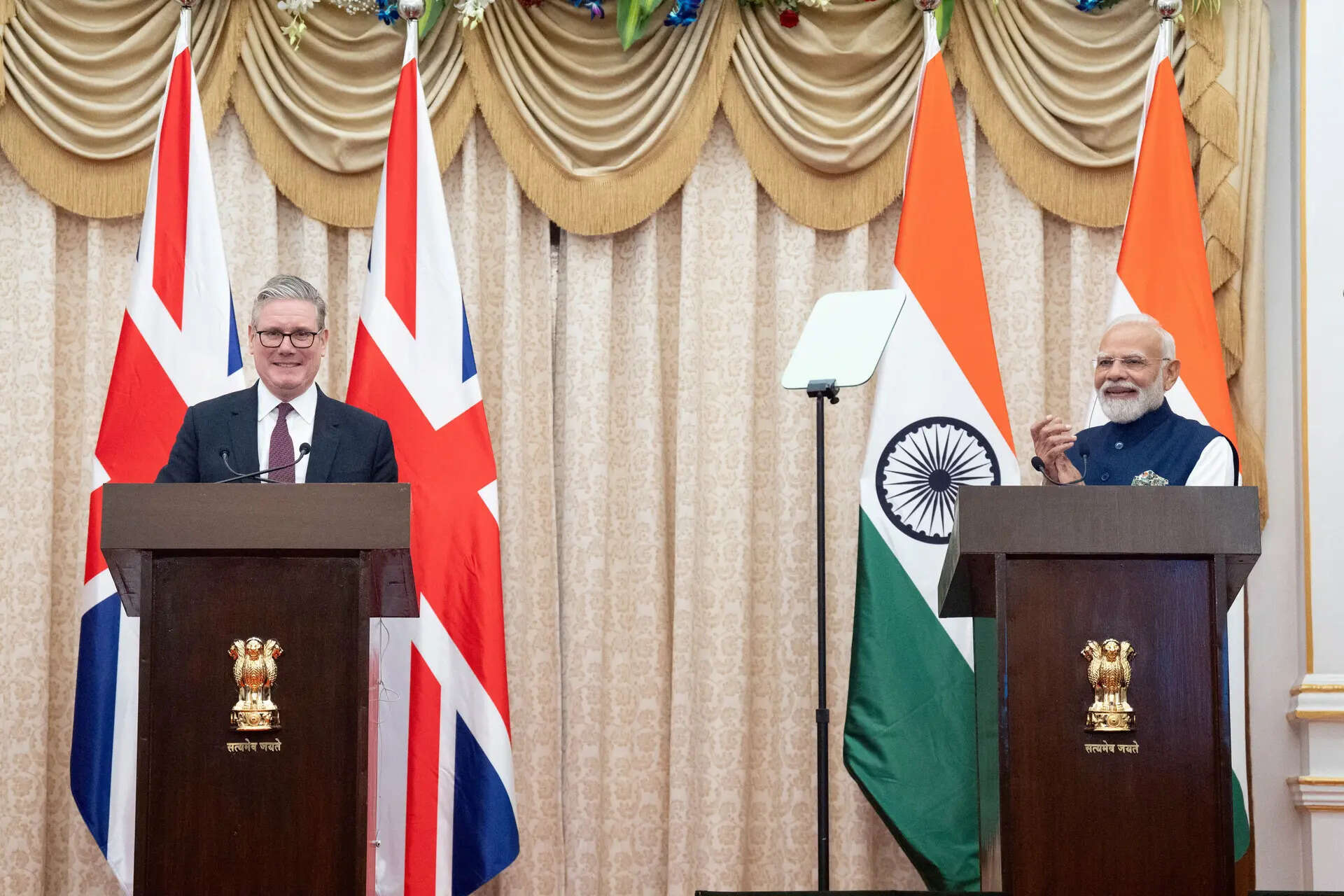

When Prime Minister Keir Starmer arrived in India on October 8 for his first official visit, it was more than a diplomatic gesture; it was a recognition of shifting global economic gravity. His meeting with Prime Minister Narendra Modi marked a pivotal moment in the recalibration of the United Kingdom’s economic and strategic worldview.

The visit followed the signing of the India–UK Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), a landmark pact designed to double bilateral trade—currently around £42 billion—within the next decade.

In New Delhi and Mumbai, Starmer carried a delegation of 125 business leaders, academics, and innovators—the largest British business contingent to travel abroad since 2018. The symbolism was unmistakable: London sees in India not merely a large market, but a long-term partner capable of underpinning Britain’s post-Brexit economic renewal.

Modi’s tone captured this new phase succinctly: “India’s dynamism and the UK’s expertise together create a unique synergy—one that promises jobs, innovation and inclusive growth for both nations.”

The Architecture of a New Trade Compact

The Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, finalised earlier this year, has provided the structural foundation upon which Starmer’s visit was built. The accord aims to reduce tariffs, liberalise services, and create more predictable rules for investment and intellectual property. In material terms, the agreement will lower trade barriers across sectors ranging from textiles and automobiles to machinery, green energy, and food processing.

Starmer described the pact as “a breakthrough moment, years in the making,” adding that “beyond the words on the page lies the confidence of two modern economies to work as equals in shaping the future.” His statement was both pragmatic and aspirational, recognising that global commerce today is less about the movement of goods than about the exchange of ideas, technologies, and trust.

The trade deal, though still awaiting full ratification, has already begun to bear fruit. The British government estimates that nearly £1 billion in new investment has flowed into the UK since its signing, creating close to 7,000 jobs. For India, the potential is broader and more diffuse—export expansion, technology transfer, and employment generation across manufacturing and services sectors.

Britain’s Search for Post-Brexit Anchors

For the United Kingdom, the visit represented a conscious attempt to reposition itself in a world where traditional trading blocs no longer guarantee growth. Brexit had severed London’s institutional umbilical cord with Europe, compelling it to rediscover partners that align with its economic and cultural instincts. In that quest, India offers a rare blend of scale, stability, and sentiment.

Starmer’s economic agenda during the visit was shaped by domestic urgency as much as diplomatic opportunity. Britain faces sluggish growth, persistent inflation, and widening fiscal constraints. By deepening engagement with India, Starmer sought to inject a measure of optimism into the British economy and signal to domestic constituencies that the Commonwealth relationship can be a source of renewal rather than nostalgia.

In his Mumbai address to business leaders, Starmer noted that “closer cooperation with India is not only about trade; it is about rejuvenating our economies and preparing our people for the industries of the future.” His reference to rejuvenation was deliberate: Britain, struggling with post-industrial fatigue, views India’s dynamism as a possible antidote to its economic malaise.

India’s Expanding Horizon

For India, the visit reaffirmed its emergence as an indispensable partner in the re-architecture of the global economy. Modi, addressing the joint press conference, underlined that “India will double trade with the United Kingdom in the coming decade and strengthen cooperation in green technologies, digital innovation and defence production.”

The potential is significant. CETA allows tariff-free access for up to 99 percent of Indian exports to the UK, particularly benefitting sectors such as textiles, gems and jewellery, and processed foods. Industry estimates suggest the agreement could generate more than 140,000 new jobs in India. These are not abstract projections; they represent a deepening of industrial ecosystems, especially in tier-two manufacturing clusters that stand to gain from easier market access.

Equally transformative are the provisions in education and technology. Nine British universities are establishing campuses in India—an outcome made possible under India’s National Education Policy.

This development not only expands academic collaboration but also signals a structural inversion: instead of Indian students flocking to British institutions, British academia is now seeking intellectual space in India. The economic significance of this shift extends beyond tuition revenue; it opens pathways for research partnerships, innovation hubs, and a future flow of talent across both economies.

The Technological and Industrial Compact

Starmer’s itinerary reflected a deliberate pivot toward technology-intensive cooperation. Under the Technology Security Initiative, the two countries announced the creation of a joint AI Centre, a Climate Tech Fund, and a Critical Minerals Industry Guild—each aimed at strengthening resilience and advancing the transition toward green economies.

Such initiatives resonate deeply with both nations’ strategic imperatives. For the UK, they offer a route to reinvigorate its research base and integrate into emerging global supply chains. For India, they align with the twin objectives of self-reliance and sustainable industrialisation. The inclusion of a joint Critical Minerals Processing Centre underlines a shared recognition that technological sovereignty cannot be achieved without secure access to essential resources.

The same logic extends to defence and maritime cooperation. A £350 million contract for lightweight missiles and a proposed Regional Maritime Security Centre of Excellence under the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative signify that economic and security architectures are converging. Economic interdependence today is not confined to trade; it extends to co-production, innovation, and the strategic management of the seas that connect markets.

Frictions Beneath the Surface

Yet the elegance of the bilateral narrative conceals persistent contradictions. Starmer’s categorical assertion that visa rules would not be relaxed disappointed Indian professionals and business groups that view mobility as integral to meaningful cooperation. The UK’s domestic politics, haunted by populist anti-immigration rhetoric, constrains its ability to translate partnership rhetoric into people-centric policy.

Other unresolved issues remain. Differences over the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, government procurement, and rules of origin could complicate implementation. India’s purchases of Russian oil and the episodic flare-up of Khalistan-related protests in the UK add further irritants. These do not derail the partnership but act as a reminder that economic engagement cannot be insulated entirely from political and societal undercurrents.

A Strategic Symbiosis in the Making

Despite these frictions, the broader trajectory is unmistakable. The relationship has acquired a new grammar—no longer defined by aid, asymmetry, or cultural nostalgia, but by mutual pragmatism and economic complementarity. The visit demonstrated a willingness on both sides to compartmentalise irritants and prioritise outcomes.

For the UK, the partnership offers access to one of the world’s fastest-growing markets and a chance to redefine its global relevance. For India, it offers investment, technology, and a bridge into European markets without compromising strategic autonomy. The economic logic, in other words, is anchored in convergence rather than dependence.

Starmer captured this spirit when he remarked in New Delhi, “This is just the beginning of a deeper economic friendship—one that invests not merely in profits but in possibilities.” Modi’s response was equally pointed: “Together we are scripting a partnership of prosperity that transcends geography and history.”

A Relationship Beyond Commerce

The economic implications of Keir Starmer’s visit to India extend well beyond trade statistics or investment tallies. They signal the emergence of a relationship defined by shared challenges and complementary strengths. At a time when the world economy is fragmented by protectionism and strategic rivalry, the India–UK partnership gestures toward a more plural and resilient model of cooperation.

Its success, however, will depend less on the grandeur of joint statements and more on the quiet architecture of implementation—customs modernisation, mobility frameworks, and innovation ecosystems. If managed with foresight and discipline, this partnership could become a template for how middle and mature powers collaborate in an era of geopolitical flux.

Both leaders have staked political capital on the idea that cooperation between New Delhi and London can deliver tangible economic dividends. In the long run, the significance of Starmer’s visit will not be measured by ceremonial optics, but by whether it can convert the rhetoric of renewal into the reality of shared prosperity.

(Anoop Verma is Editor-News, ETGovernment)