Before we begin

This is a story about gallium’s discovery and how it played a part in the acceptance of the then newly invented periodic table. Gallium was discovered by French chemist Paul-Emile Lecoq de Boisbaudran and you probably associate the periodic table with Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev. Why then are you staring at the picture of German chemist Lothar Meyer and his not-so-popular periodic table? There’s a simple answer to that.

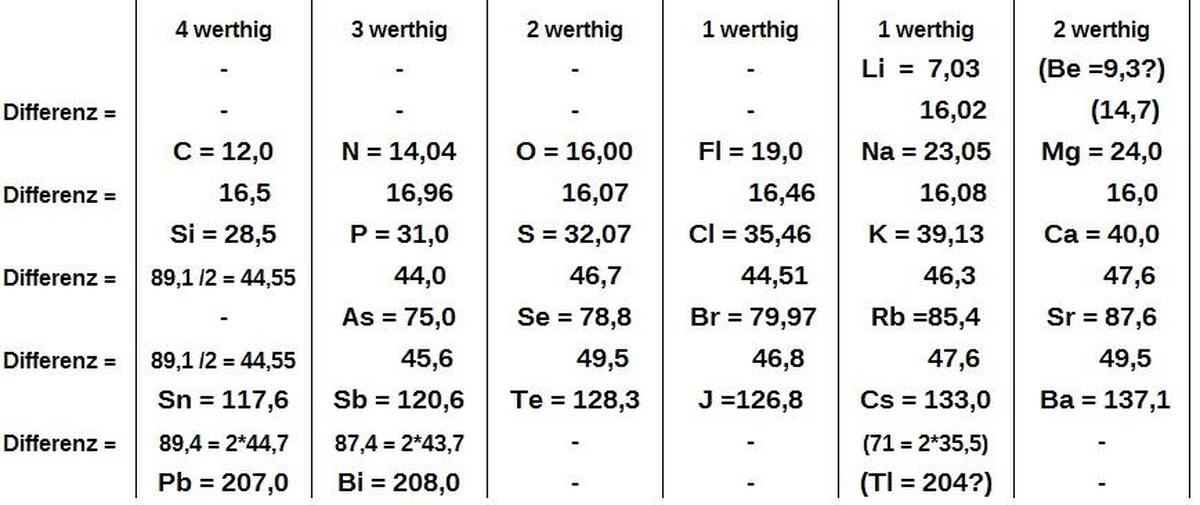

Meyer’s periodic table.

| Photo Credit:

Kawarayaki / Wikimedia Commons

Like many developments in the fields of science and technology, the invention of the periodic table didn’t take place in isolation. Even before these tables were formed, a number of people were already busy finding relationships between various elements that were already known. There were certain triads known in which the atomic weight of the element in the middle was the average of the ones on either side. Chemists were aware that at least some elements came as families, with the halogens — fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and iodine (astatine was discovered only in 1940) — being one such family.

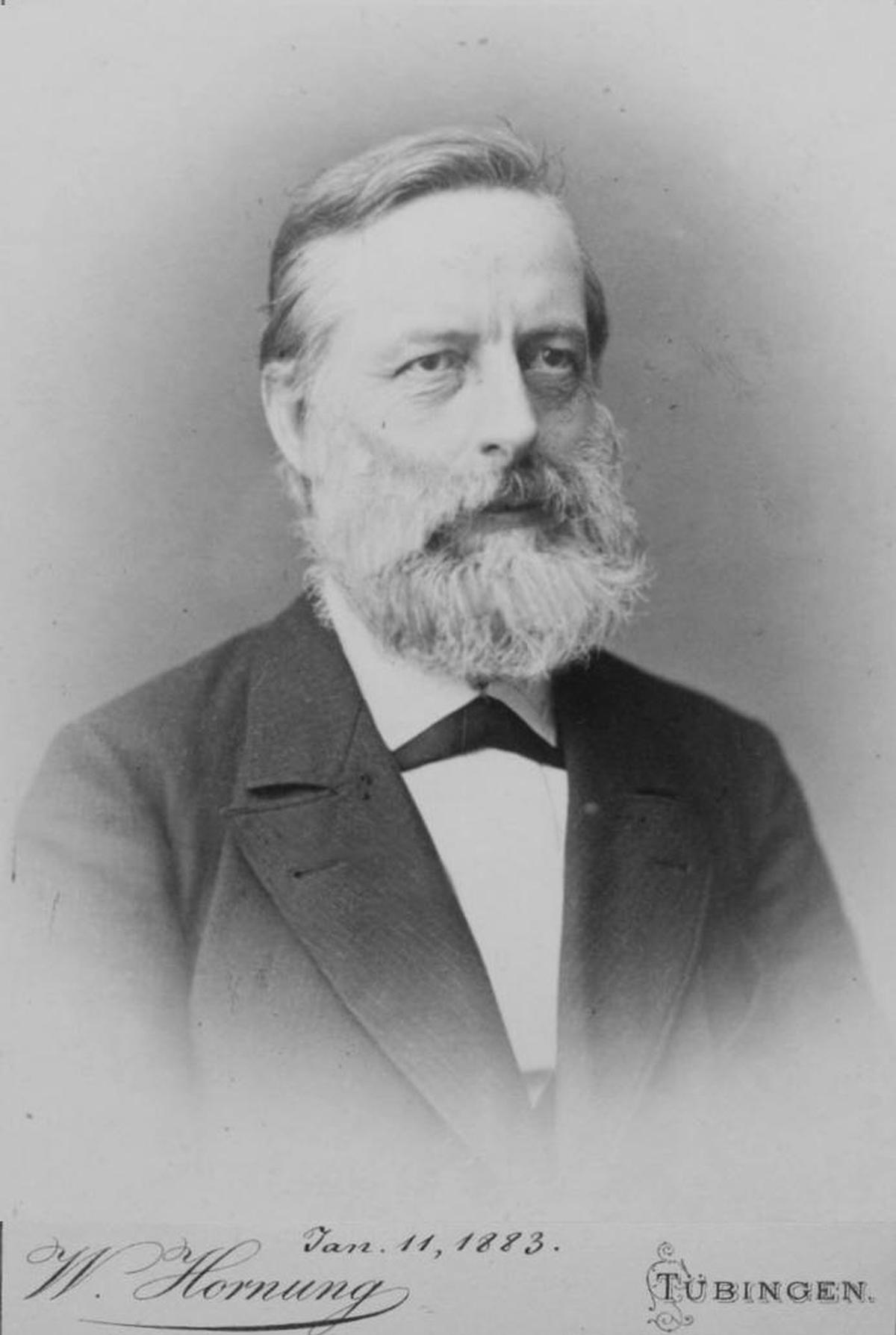

Lothar Meyer.

| Photo Credit:

Wilhelm Hornung / Wikimedia Commons

Even before Meyer published his first edition in 1864, there were others. Alexandre-Emile Beguyer de Chancourtois, a French mining engineer, created a system of his own in 1862. After drawing a diagonal line on a piece of graph paper, he placed elements along the line based on increasing atomic weights. He wrapped this sheet around a cylinder, and when a vertical line was dropped down the sheet, elements with similar properties were linked. Quite a visual helical structure, is it not? Including Meyer’s and Mendeleev’s, there were at least six systems to order elements that were stated in the 1860s alone.

Hailing from a scientifically inclined family, Meyer had followed a predictable path to become a professor in Germany. His 1864 version of the periodic table included a table of 28 elements arranged by increasing atomic weight and divided into six families by valence.

Mendeleev steps in

How Mendeleev arrived at his periodic table is well documented. In fact, it is more than just well documented as Mendeleev went out of his way to keep all his notes, records, and letters — literally everything — when he started realising the potential of his periodic table and knew it would make him famous. In any case, a brief recap would go something like this. Having taken an unconventional route to become a professor in chemistry, he found himself having to teach inorganic chemistry in the mid 1860s. Unimpressed with the quality of textbooks available in what was a relatively new field for him, he focussed on writing one himself and thereby was looking to organise elements.

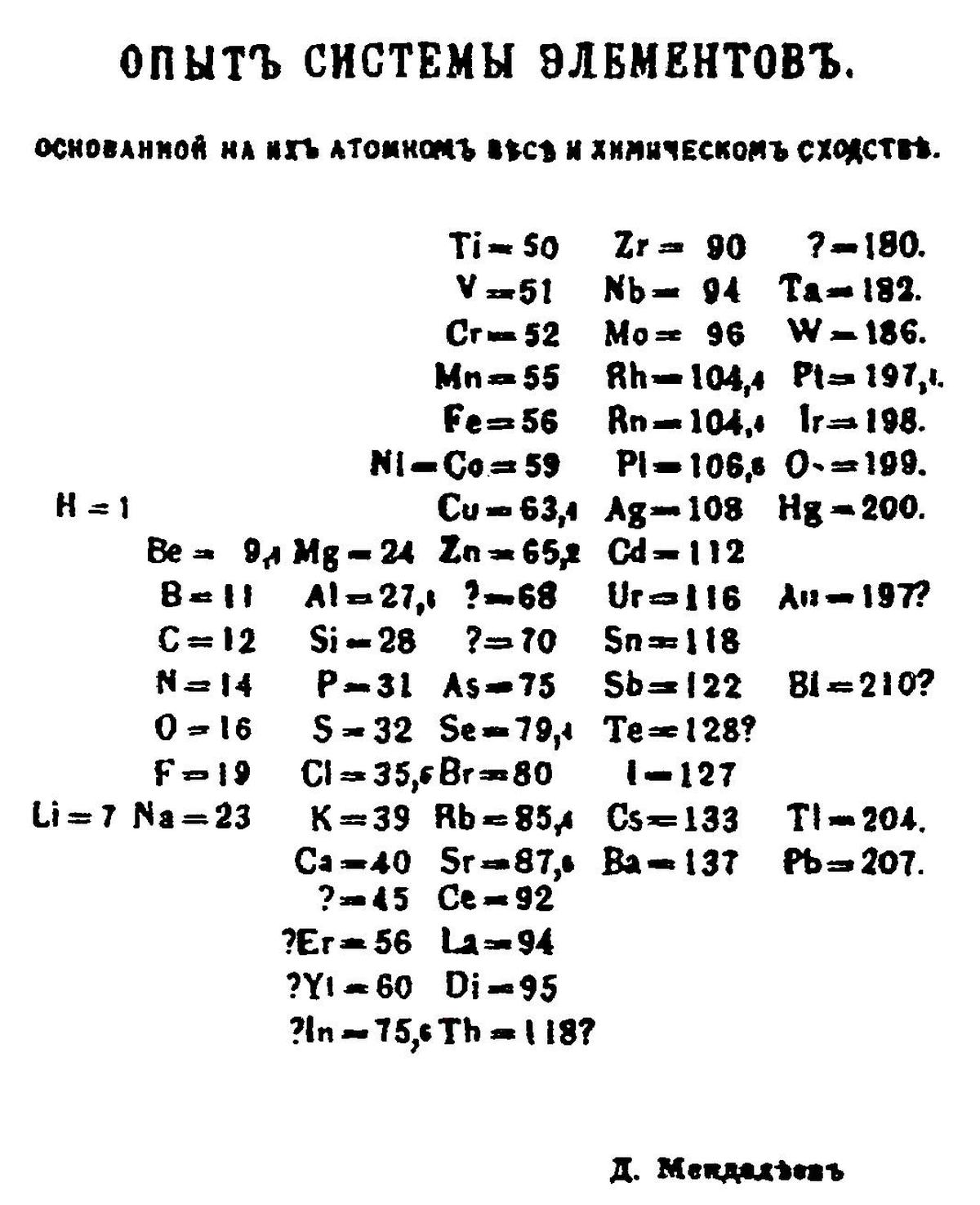

Mendeleev’s 1869 periodic table

| Photo Credit:

Dmitri Mendeleev / Wikimedia Commons

It was in such a climate that he arrived at what he did in 1869. Mendeleev is said to have written down each of the 63 elements known at the time along with individual properties on separate note cards. He is then believed to have played a game of chemical solitaire or patience, arranging each of these cards in vertical columns from lower to higher atomic weights.

Even though there’s no evidence for Mendeleev having done exactly this (given he saved everything in relation to his table, there’s no trace of these cards), it certainly does now mark the birth of the periodic table. And when he encountered gaps — three to be precise — he filled it with a question mark and a rough estimate of atomic weight before heading to the next element. It was, in fact, only in 1870 that he began to offer detailed predictions for what he called eka-elements — eka-aluminium, eka-boron, and eka-silicon, which filled the gaps next to aluminium, boron, and silicon.

De Boisbaudran’s discovery

Paul-Emile Lecoq de Boisbaudran.

| Photo Credit:

Wikimedia Commons

Even Mendeleev himself wasn’t quite sure as to when his predictions would turn out to be reality. He expected them to come true in an uncertain date in the future, yes, and at best hoped to be still alive when it happened. The way the reality panned out, however, would have likely surprised Mendeleev as well, as much as everyone else. The discovery of an element that would pave the way for the acceptance of the periodic table came as early as 1875.

Frenchman Paul-Emile Lecoq de Boisbaudran took to the family business as a 20-year-old and spent his spare time with physics and chemistry. The tables flipped, however, when their business prospered, affording him plenty of time to indulge in experimentation.

Rapid dissemination of information

When working with a large amount of zinc ore that he obtained from a mine in Hautes-Pyrenees, de Boisbaudran discovered a new element on August 27, 1875. The months that followed saw rapid progress, thanks largely to the journal Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des seances de l’Academie des sciences. First, the original spectroscopic findings of de Boisbaudran were published. Next, the production of metallic gallium by de Boisbaudran made its way.

The word “excited” would probably be an understatement to describe Mendeleev’s emotions when he encountered these findings. The Russian was convinced that gallium was in fact one of the eka-elements that he had predicted — eka-aluminium that he had placed in the gap next to aluminium. Mendeleev’s statement in Comptes rendus — Remarques à propos de la découverte du gallium — was published on November 22, 1875. Mendeleev claimed that his predicted eka-aluminium had been discovered and that it was in fact gallium.

De Boisbaudran initially saw Mendeleev’s statement as a claim to the discovery and he responded in the negative, again in the journal. The characteristics of gallium, however, matched with Mendeleev’s predictions and the only discrepancy too turned out to be an experimental error. By December 1875, de Boisbaudran had firmly established gallium, having finally published further detailed spectroscopic and chemical description of the element, all of which closely matched the predictions.

Mendeleev has his way

In a little over a decade following gallium’s discovery, all three of Mendeleev’s eka-elements had been discovered. Eka-boron was discovered by Swedish chemist Lars F. Nilson in 1879 and called scandium; and eka-silicon was discovered by German chemist Clemens Winkler in 1886 and called germanium. Mendeleev’s predictions had been proven emphatically.

Portrait of Dmitri Mendeleev.

| Photo Credit:

pixel17 / flickr

But was this prediction the most important part of the periodic table? Or was it identifying the periodic change in the properties of elements when organised based on their atomic weights, which Meyer had also done?

Lost in translation

Mendeleev and Meyer had been involved in an heated argument over priority for the periodic table from the 1870s. The fact that Mendeleev’s Russian work when translated and published in German in 1869 had used the word that meant “stepwise” rather than “periodic” for the change in properties was hotly contested. With much of the world seeing the merit in the periodic table by the 1880s and accepting it, it was left to Mendeleev to convince everyone that prediction was a crucial differentiator when looking at priority as to who created the system.

As Meyer and Mendeleev had arrived at their results independently, chemists of the era often shared the credit for the creation of the periodic table among both men. In fact, both men jointly received the Davy Medal of the Royal Society in 1882 for the discovery of the periodic relations of the atomic weights.

Things, however, began to change following Meyer’s death in 1895. With Meyer no longer around to argue against him, Mendeleev continued to claim sole ownership over the creation of periodic table until his own death in 1907. This, followed by decades when the Soviet Union grew in stature as a scientific superpower, saw the scales tip firmly in Mendeleev’s favour. So much so that Mendeleev is not only given sole credit for the creation of the periodic table these days, but few actually know about Meyer’s contribution.

Meyer’s first name

Lothar Meyer, unlike many others, is almost always referred to without his first name. He himself never used his first name Julius, instead preferring his middle name Lothar. Throughout his life, he was known simply as Lothar Meyer.

As he personally preferred to use his middle name in both his personal and professional lives, the practice continues to this day. All references to him — be it historical or about his scientific work — are now done as Lothar Meyer.

What is this eka?

In case you were wondering if this “eka-” has an Indian connect, it most certainly does. A Sanskrit prefix meaning “one,” Mendeleev used “eka-” for elements he predicted would exist based on his periodic table. He applied it to elements he believed would be “one step beyond” an element that was already known at the time.

French chicken

No, we aren’t getting into culinary chemistry here. It’s more a play on the name of the element in question, gallium, and how we arrive at this name.

So you might have heard that de Boisbaudran named the element after his country, France. Gallium is derived from the Latin word Gallia (gaul), which refers to France, and hence it fits.

It didn’t take long for people to start accusing him for naming the element after himself though. In case you are wondering how that works, Boisbaudran’s family name “Le coq” is French for “rooster”.

While he personally denied the accusation vigorously, we’ll never know if de Boisbaudran named gallium after his country or himself.

Many elements in the periodic table have been named after people, and it includes one named after Mendeleev too.