The passage of time, especially that inhabited by humans, has often been named based on the materials we use during that time. The Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages are, for instance, a three-age system that divides human prehistory based on the primary materials in use then. It makes sense as the materials we use helps fashion the tools we create. It is these tools that we then use to shape the world around us.

By that definition, we well and truly live in the Age of Plastics now, also referred to as the Polymer Age. While thousands of natural polymers exist, human-made versions are a much more recent phenomenon. Bakelite, the first fully synthetic plastic, was invented only in the first decade of the 20th Century, by Belgian-American chemist Leo Baekeland.

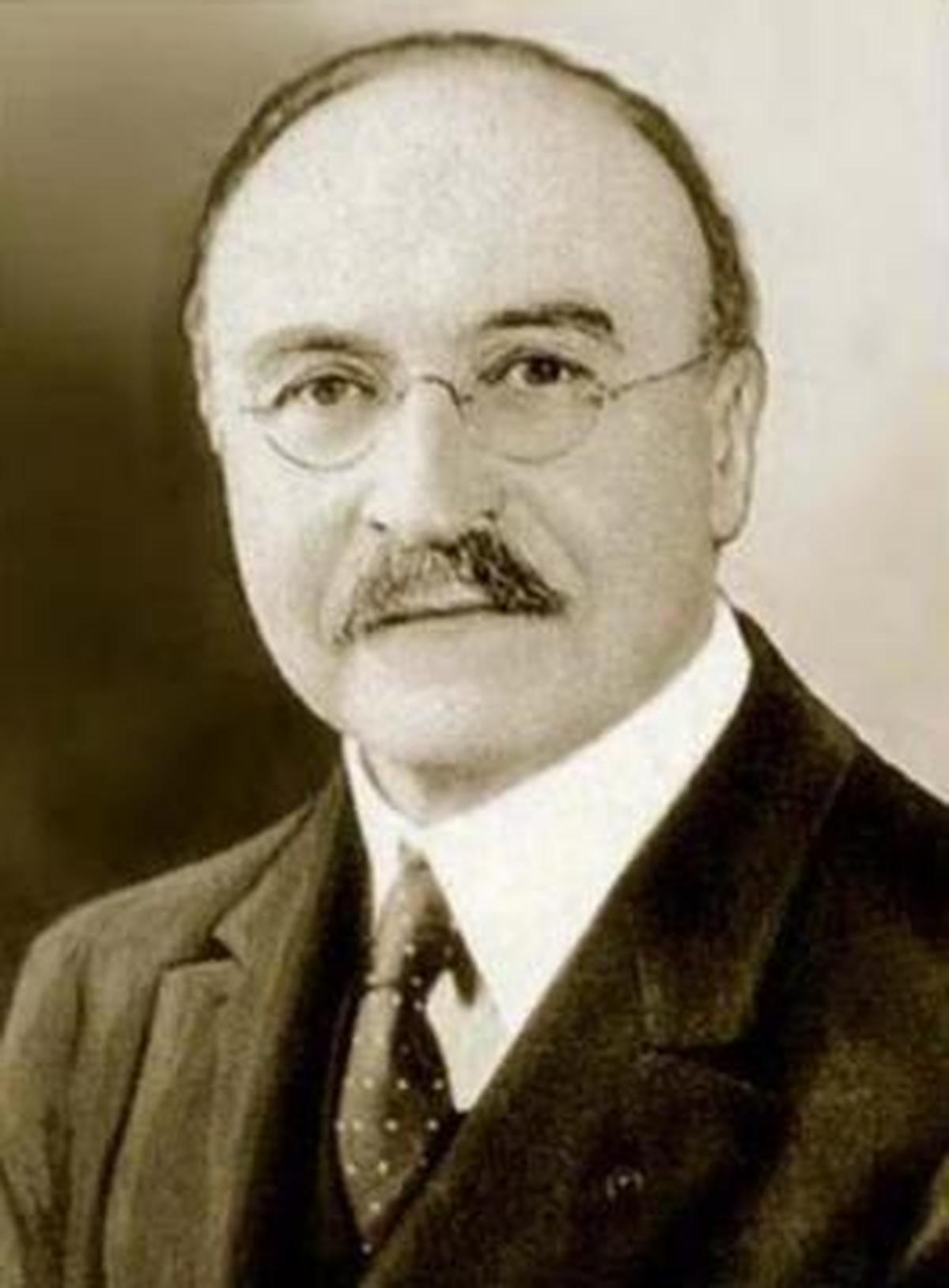

Mother’s insistence

Belgian-American chemist Leo Baekeland.

| Photo Credit:

Paralaloa / Wikimedia Commons

Born in the Flemish city of Ghent on November 14, 1863, Baekeland was the son of a cobbler and a maid. His father, the shoemaker, was against his son’s wish for an education and had him apprenticed to a fellow shoemaker at the age of 13. Baekeland’s mother, a domestic helper, insisted on her son being allowed to study at a government high school, paving the way for his future success as an inventor.

Studying diligently, Baekeland made his way to the University of Ghent by 1880, having acquired a city scholarship. He studied chemistry and physics and found an able mentor in the form of Theodore Swarts.

When Baekeland became an assistant professor of chemistry at the age of 24, Swarts saw it as the start of a great academic career. Baekeland, however, was less interested in pure chemistry, and was more drawn towards potential applications. This created some friction between the duo.

Finds his love

While there were quarrels between Baekeland and Swarts on one side, there was love between Baekeland and Swarts on the other. For Baekeland fell in love with his mentor’s daughter Celine and the two got married. As Baekeland won a travelling scholarship for academic study abroad, the young couple left for the U.S. soon after. This same fellowship also allowed him to visit universities in England, Scotland, and Germany.

It is interesting to note that as a youngster, Baekeland was enamoured by The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, with this work sparking his lifelong love for America. He became a citizen of the country by 1897 and soon became a notable member of the country’s chemical industry.

Chandler’s helping hand

After the fellowship, they settled in New York City and Baekeland found support in the form of Columbia University professor Charles F. Chandler. It was Chandler who recommended him to a position at a New York photographic supply company, a position that would literally transform Baekeland’s life in the years to come.

Based on his experience at the photographic house, Baekeland made his first major successful invention while working as an independent consultant. He came up with a new kind of photographic paper that he called Velox. Velox could be enabled in gaslight rather than sunlight, thus enabling images to be developed using artificial light.

When George Eastman of the Eastman Kodak Company bought the rights to Velox for $750,000 (nearly $30 million in today’s money) by the end of the 19th Century, Baekeland had made his fortune. Baekeland, however, had to accept to Eastman’s terms of not developing any more photographic technology as part of the sale agreement.

“Cakelyzer” was a cake at the fifth anniversary of the Chemical Heritage Foundation‘s museum opening in Philadelphia. The cake is modelled after an actual object in the museum’s collection, a replica Bakelite oven or “Bakelizer”, invented by Leo Baekeland.

| Photo Credit:

Conrad Erb / Science History Institute / Wikimedia Commons

Turns to polymers

The loss to photographic technology turned out to be a gain for the polymer industry as Baekeland, now financially free to pursue a field of his liking, channelled his time and efforts elsewhere. Baekeland, in fact, went after more money when he chose the field of synthetic resins as the problems confronting the field, in his opinion, offered “the best chance for the quickest possible results.”

By the turn of the century, chemists acknowledged the potential of natural resins and fibres, but made little headway in terms of synthetic substitutes. Baekeland pored over the theory and performed his research in a systematic fashion, documenting the results meticulously.

Baekeland tasted success again when he switched his focus from trying to create a wood coating to trying to impregnate wood with a synthetic resin, thereby strengthening it. By controlling the effects of temperature and pressure, while at the same time keeping a tab on the type and proportion of phenol and formaldehyde mixed, Baekeland was able to produce polyoxybenzylmethylenglycolanhydride.

When Baekeland said Bakelite could be put to use in a 1000 ways, he meant it! A picture of an advertisement for Bakelite in The Saturday Evening Post of January 1923.

| Photo Credit:

Karel Julien Cole / flickr

Bake up a storm

Baekeland observed that the key to arriving at the final product were machines that subjected the earlier stages to right amount of heat and pressures, machines that he called Bakelizers. He filed a process patent for making insoluble products of phenol and formaldehyde in July 1907 and obtained it on December 7, 1909. He gave the product the catchy name of Bakelite, naming both the product and the machine instrumental in its preparation, unsurprisingly, after himself.

The public announcement of Bakelite’s invention was done in a lecture before the New York section of the American Chemical Society on February 8, 1909, months before he was granted the patent. The fact that it could be pressed directly into whatever final shape was required meant that it soon found a multitude of different uses, and was especially sought after in the automobile and radio industries, which were just flourishing themselves.

Picture of a 1933-34 model Philips radio in Bakelite shell.

| Photo Credit:

Robneild / Wikimedia Commons

From telephones, radios, and cameras to coffins and medical training equipment, Bakelite found its way everywhere. The first synthetic plastic, in that way, was setting the perfect precedent for its descendants as plastics continue to operate in an all-pervasive manner to this day.

When his son George Washington Baekeland (didn’t we tell you he loved America?) preferred not to head the business, Baekeland sold his company for a sum of $16.5 million (over $350 million in today’s money) to Union Carbide (if the name of this company rankles you a bit, that’s because of the 1984 Bhopal gas tragedy) in 1939. He retired thereafter to, among other activities, sail his yacht Ion. Having been responsible for the birth of the Age of Plastics, he saw the beginning of its proliferation through World War II, dying in 1944 after a lifetime of discovery and development.

Published – December 07, 2025 12:51 am IST