Cities around the world, but especially in Asia, are growing upwards faster than they are spreading outwards, a new study published in Nature Cities has found. In an increasingly urban and urbanising world, taller buildings can accommodate more people in less space but they can also negatively affect existing infrastructure, the local environment, and even the climate.

“Urban population, roughly from 1990 to 2020, increased by about 2 billion people,” Steven Frolking, an earth scientist at the University of New Hampshire and the lead author of the current study, said. “So cities have had to grow in order to accommodate those 2 billion people. The question is, how have they grown?”

A soaring volume

A team of earth and urban scientists came together to answer this and look at more than 1,500 cities around the planet from the 1990s to the 2010s. They used remote-sensing satellite data to gather information about cities’ vertical growth and two-dimensional (2D) outward spread.

To understand how cities grew, the team examined their footprint: the rate at which ground area was getting covered by buildings. They also used data from scatterometers — satellite-borne sensors that send out pulses of microwaves to the earth’s surface and collect the data reflected back — to get a sense of how city structures have changed in volume.

“So by combining these 2 data sets, we thought we could get a better picture of how cities are growing both laterally and vertically,” Dr. Frolking said.

They found that the rate at which the 2D spread was increasing wasn’t as high: that is, cities weren’t expanding as much as they used to. But the microwave data suggested the volume of city structures was soaring.

‘Only paper in the literature’

“The microwave data is sensitive to both lateral growth and vertical growth, but we see it accelerating, growing at a more rapid rate in most cities over this three-decade period,” Dr. Frolking explained. “So if the cities are not accelerating in the rate at which they cover the ground with buildings, but they’re building volume — which is what we think the microwave correlates to most reliably — the implication of that is that it’s vertical [growth].”

A view of Shanghai, China, on January 8, 2020.

| Photo Credit:

Road Trip with Raj/Unsplash

Based on their analysis, the researchers found an upward-growing trend of cities worldwide, with some east Asian cities, especially in China, in the lead. Cities with populations in excess of 10 million people had more prominent vertical growth, and this effect became more pronounced in the 2010s.

“This is the only paper in the literature looking at upward growth for such a long-time span and for this large sample of cities,” Richa Mahtta said in an email. A co-author of the paper, she is a Yale graduate student with Karen Seto, one of the world’s leading experts on the topic and also a co-author of this study.

“3D urban growth could open a new paradigm for remote sensing research and its applications in advancing our understanding of urban growth and its impacts on local climate,” Ms. Mahtta said.

‘It’s a nice attempt’

“Up to a certain extent, a city can grow, right? Beyond a point, it will start to densify,” said H.S. Sudhira, who has a PhD in urban planning and governance from the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, and is currently the director of Gubbi Labs. “What is critical from a more policy and pragmatic view is to understand the threshold at which it shifts from outward growth to densifying in a way that it goes vertical.”

“It’s a nice attempt to really look at it from a global context,” he said.

Indian cities did not show a uniform upward growth, with only the large ones with more than 5 million people showing upward and outward or just outward growth, mostly in the 2010s.

“In India in particular, there’s much more regulation compared to China, in building heights that cities will allow. So cities haven’t been able to grow as rapidly vertically in India as they have been able to in, say, East Asia or Southeast Asia,” Dr. Frolking said.

In Delhi, for example, most of the growth was outwards in the 1990s and 2000s, with some upward growth in the 2010s.

‘Cities aren’t like naturally-occurring beings’

Surajit Chakravarty, an urban planner and policy scholar at IIT Delhi (speaking in a personal capacity), believes we must exercise caution before ascribing a global trend to cities in very diverse contexts.

“This is a very interesting paper about the morphology of cities from a comparative international perspective,” Dr. Chakravarty wrote in an email to this correspondent. “But cities are not like naturally-occurring beings. Their shapes and forms are not dictated by rules of nature but rather by policies, regulations, jurisdictional boundaries, economic conditions, and historical patterns. These are all socially constructed. In addition, physical geography plays an important role.”

Detailing some of the regulations to which Dr. Frolking alluded, Dr. Chakravarty said that in some places like New Delhi, the most expensive central Delhi real estate — or the “Lutyens bungalow zone” — is very well protected. This leads to most of the taller buildings coming up in the outskirts of Delhi, for example in Noida and Gurugram. Similar heritage areas or protected zones may exist in central parts of many other South and Southeast Asian cities as well. This situation is not comparable with most cities in North America.

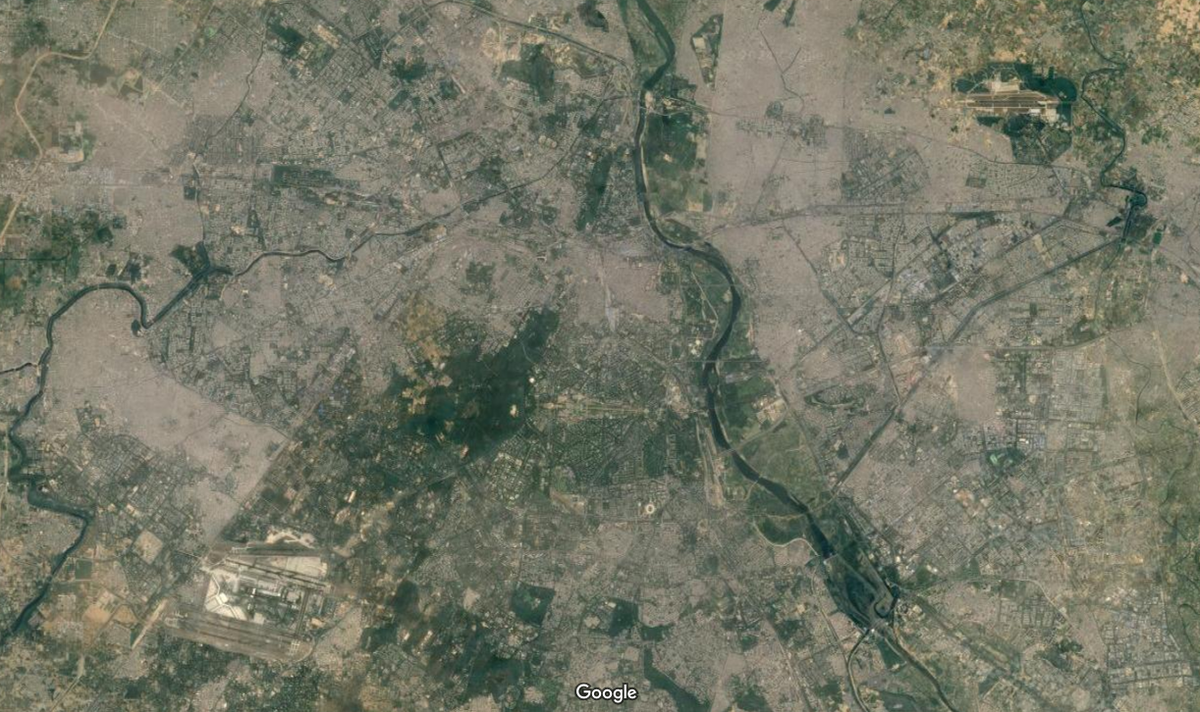

A bird’s eye view of New Delhi in 2023.

| Photo Credit:

Google Earth

Another reason the current paper could be missing out on some areas of Indian urbanisation is because of its low resolution: the scale used in the paper is about 5 km. “It’s a very coarse resolution for India,” Dr. Sudhira said. But he admitted that increasing the spatial resolution for a global study like this would have generated a massive amount of data too complex to analyse.

Cities are less efficient

“In India, a large part of the urbanisation is occurring outside the study’s parameters, in very small towns and through the process of villages turning into urban places,” Dr. Chakravarty pointed out.

Vertical growth can increase population density, and if the costs are reasonable, can also house many more people (i.e. greater density). But such growth needs to be supported with more jobs and good public transport to reduce transport emissions and improve walkability. Strong infrastructure with decent sewage and water systems are also required to sustain a large number of people. Taller buildings will also need specialised resources and will have a greater energy demand.

While growth is important, how this is achieved — keeping sustainability and climate resilience in mind — is crucial in this time of unprecedented climate change. Despite the rapidly rising rates of urbanisation, Dr. Sudhira is thankful that the majority of Indians are still in rural, dispersed settlements, which he said are more efficient and climate-resilient.

More tall buildings without any tree cover can also cause an urban “heat island” effect, which can affect temperatures and rainfall in cities. A study published on June 11 in the Journal of Advances in Modelling Earth Systems studied Shanghai’s growth and reported more built-up area could slow wind speeds by up to half.

“It’s not easy to say doing it this way is better than that way. There are trade-offs in all of these things,” said Dr. Frolking. “We want to be able to know how cities are developing, have a way of looking at these trajectories, and see if there are patterns that can help us anticipate energy and resource use. 3D urban structure has implications for a whole bunch of factors, including disaster relief, sustainability, and liveability.”

Dated master plans

Fire personnel evacuate the residents of Rainbow Layout after the Halanayakanahalli Lake breach following heavy rains, on Sarjapur road, Bengaluru, September 5, 2022.

| Photo Credit:

Murali Kumar K./The Hindu

“We [India] seem to be following the trajectory that China is going through, at least some in terms of the population and to some extent some bit of industrialization and economic growth as well,” Dr. Sudhira said. “In that context, I would see this paper as an alarm call; we need to really sit back at the drawing board and say, should we really allow for more high rise and what should be the policy on that?”

Most cities and States in India, including Bengaluru, are working with dated master plans, which decide how land will be occupied by different urban structures. Most existing planning laws don’t even acknowledge transportation, energy, water, resources, waste-water management, and solid waste, according to Dr. Sudhira.

“We need to revisit and rewrite our master planning acts, with a more progressive law that is enforceable and can stand the test of time,” he said. “It should encompass all of these things and also aspects of climate change, because I think we’re at a time where you can’t ignore climate change.”

“There is no one-size-fits-all approach with cities,” Dr. Chakravarty added. “India needs trained planners to make locally grounded decisions keeping in mind the needs and aspirations of the people, and the objectives of sustainability and liveability.”

Rohini Subrahmanyam is a freelance journalist in Bengaluru.