Manisha Koirala claims she is a slouch on any ordinary day. “I can’t sit upright!” she chuckles. On the other end of the Zoom call, the 53-year-old actor appears relaxed, her hair tied back in a lazy bun, her eyes filled with warm candour behind her oversized spectacles. It is in stark contrast to Mallikajaan, the head of a glamorous house of courtesans in pre-Independence India, the character Koirala portrays in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s ambitious project Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar. The web series, releasing on Netflix on May 1, is her second collaboration with the filmmaker after the iconic Khamoshi: The Musical (1996).

One of the biggest Indian movie stars in the 90s, Koirala has essayed several unforgettable characters in films like 1942: A Love Story (1994), Bombay (1995), and Dil Se.. (1998). After a tumultuous battle with cancer and a slew of personal issues, she slowed down in the last decade, appearing in only a handful of films, yet not failing to surprise the audience, as she did with Dibakar Banerjee’s superb short film in the anthology, Lust Stories (2018). “I want to go beyond what I typically get,” says Koirala of her ambition as an actor. Edited excerpts:

Has your approach to acting changed over the years?

When I was younger and working in song-and-dance movies, portraying the typical Bollywood heroine, I could rely on my instincts and go with the flow. If a film required me to rehearse, I did that. For Khamoshi, I spent a couple of months learning sign language. Now, I am in that stage where I feel method acting works for me. I want to be mentally, emotionally and physically well-prepared for a role. Since I do not take up many projects now, I have the time to do that.

How did you prepare for ‘Heeramandi’?

Mallikajaan, my character, speaks chaste Urdu, and she has long and elaborate dialogues. So my first concern was how to get control over the language. Upon my request, Munira ji, a scholar who has studied and researched the Tawaif culture, came on board as a diction coach. She explained to me that these courtesans were not sex workers but the epitome of grace, manners and culture. They were gifted singers and dancers.

A still from ‘Heeramandi’.

I realised I could not be Manisha Koirala for one bit — I am lazy and tomboyish, and care two hoots about body posture. My whole demeanour had to be different. So I took inspiration from my grandmother, a Bharatanatyam dancer, and my mother, a Kathak dancer. Growing up in Varanasi, I have seen many classical dancers and musicians. To become Mallikajaan, I remembered and collected all these details. I developed an emotional, mental and physical language. Sanjay and his team had already created her external world through extensive research. As an artist, I just had to follow his lead and fit into that world. Sometimes, he would correct me, “You are not Gayatri Devi, you are the head of the Kotha!” pointing out that I was being too feminine.

In this phase of your career, what are the roles you think of as difficult?

I love difficult. I am a greedy actor. I want to go beyond what I typically get. I follow world cinema, and when I see a great performance, I think ‘Oh, I want to do that’. In my 20s, I watched one of my first Broadway shows — Miss Saigon. I was in awe of that central performance. I love Meryl Streep in so many films. I love films of Wong Kar-wai and Almodovar — In The Mood For Love and Women On The Verge of A Nervous Breakdown, respectively.

You and Sanjay Leela Bhansali go back a long way. What is your perspective on his career trajectory?

Sanjay is a filmmaker who has such a splendid career arc. We did Khamoshi, a beautiful, simple and yet profound film. Two years ago, CODA, a European film that narrated the same story — the one he wrote 28 years ago — won at the Oscars. His characters are so complex and layered. They undergo conflicting emotions, neither black nor white.

Manisha Koirala (second from left) with director Sanjay Leela Bhansali and her co-stars from ‘Heeramandi’.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Isn’t there a shortage of Bollywood films that look into the lives of women?

We have had films like Umrao Jaan, but unfortunately, there is very little space for such works. First of all, actresses have a shorter career span. This is not a problem unique to Bollywood, but is the case with film industries worldwide. Recently, Crew did superbly at the box office. I watched it in a theatre. Kudos to all three actresses and the filmmaker. But we need more. See, a filmmaker like Sanjay could make any film, but he chose to make Heeramandi, which is about women.

‘Heeramandi’, like ‘Bombay’ or ‘Dil Se..’, engages with the idea of nationhood. What is your take on it, especially since we are now witnessing a surge of nationalist and propaganda films in Bollywood?

I am not in a position to comment on this topic. I would stay away from controversy as much as possible. Nationalism is important. Propaganda, I think, is the wrong term. You should be proud of who you are. Your heritage is where you stand. Everybody is entitled to their own opinions about it.

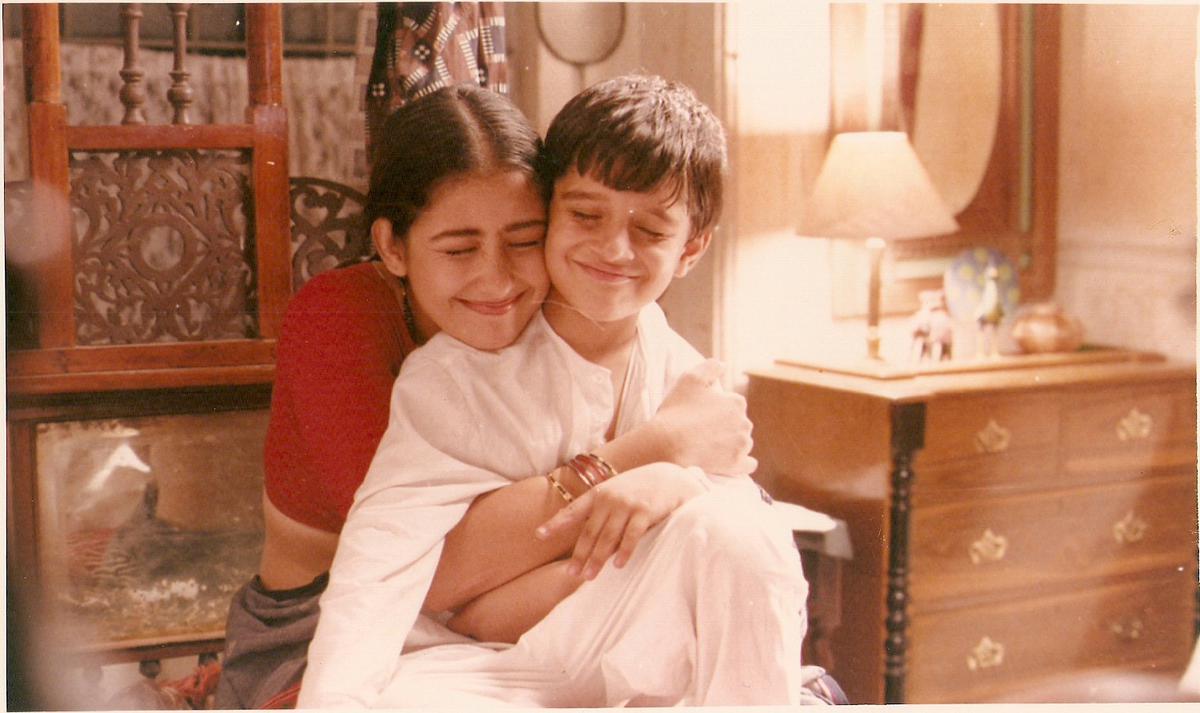

A still from Mani Ratnam’s 1995 film ‘Bombay’.

Your career has been through multiple breaks and upheavals. Where do you aspire to go from here?

The battle with cancer made me think of my mortality. After that, I wanted to slow down. As an actor, I have had a rich journey, and my heart is full. If a filmmaker I truly trust offers me something exciting, I will take it up in a heartbeat. Otherwise, I am happier doing nothing. I will travel, read, do organic farming, hike, and live away from the limelight.

The Internet has completely transformed celebrity culture. How do you deal with social media, promotional interviews and airport looks?

I do my best to adapt to the new generation. [Laughs] I could probably write a comedy about an actor from the 90s trying to fit in with the latest trends, like the airport look, only to realise that she is a misfit. She will try hard, thinking, ‘Oh, this must be how it works’, and fail miserably. After a lot of stumbling, she concludes: ‘Okay, this is me, this is how I am going to be!’ because authenticity is what really matters.

You have dabbled in film production earlier. Do you wish to make another film?

Producing the film [Paisa Vasool, 2004] was a traumatic experience. I was too naive; I did not realise what it takes. Somehow, we managed to pull through. I never produced a film again because I lost money on Paisa Vasool. I also realised that film production entails certain areas I do not want to be involved in. But times have changed. The industry is much more professional now. One does not have to go door-to-door to find distributors or deal with all the hurdles that I went through. If I get into production again, it will be well-planned and thought out.

The interviewer is a film critic and independent researcher.