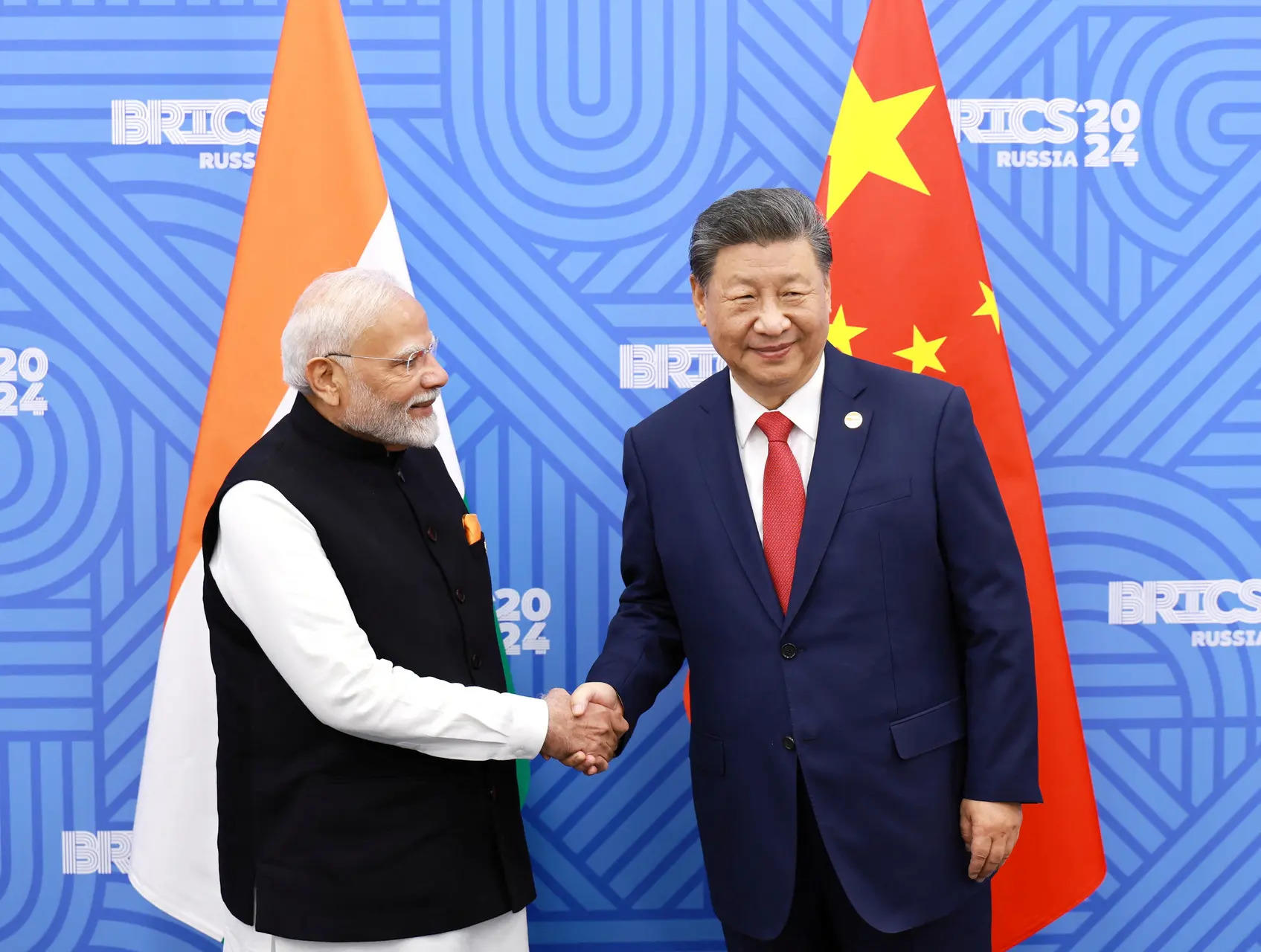

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Xi Jinping, the Chinese President, met in Kazan, Russia, on October 23, 2024 on the sidelines of the 16th BRICS Summit. This was the first formal bilateral meeting since 2019. The relation between the two countries was strained due to the 2020 border clash in Ladakh.

This meeting was a significant diplomatic move that indicates a potential thaw in Indo-China relations. Both the leaders expressed a commitment for enhancing cooperation and addressing key issues. While Prime Minister Modi emphasized the importance of “mutual trust, mutual respect, and mutual sensitivity” as the foundation for improved ties, Xi Jinping highlighted the “need for managing differences constructively and fostering development goals for both countries.”

While there is cautious optimism about future cooperation, fingers are crossed about trade and investment improving in the near future. The recent improvement in Indo-China border relations shows a ray of hope in trade and investment in electric vehicles (EV) and components thereof. However, it is still uncertain if the accord will lead to any shift in India’s trade policies related to the entry of Chinese electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers into the Indian market; conversely Chinese policy of technology transfer and investment in India.

The situation has got further complicated with the election of Donald Trump as the President of the USA.

In April 2020, the Indian government mandated that investments from any country sharing a land border with India, including China, require government approval. This change came in response to national security concerns, as well as to prevent opportunistic takeovers of Indian companies.

Chinese investments now cannot proceed through the automatic route. The new rules apply to all sectors, meaning that any Chinese entity or an entity based in another country with a Chinese beneficial owner requires government approval to invest in India. This applies to new investments, acquisitions, and even incremental funding in existing investments.

Certain sectors that are considered sensitive to national security, like telecommunications, infrastructure, data management, financial services, and defence, are scrutinized heavily. Chinese investments in these areas are either restricted or allowed only under strict conditions to ensure compliance with India’s security requirements. After the 2020 border skirmishes, India banned numerous Chinese apps citing data security concerns.

This increased scrutiny extends to FDI in tech-related sectors, especially in areas involving data storage, telecommunications, and technology infrastructure. Chinese firms like Huawei and ZTE, for example, have faced significant regulatory hurdles in India’s telecommunications sector due to concerns about cybersecurity risks.

Further, infrastructure projects near sensitive areas, such as border regions, are usually off-limits to Chinese companies. Chinese entities and investors are also restricted from making Foreign Portfolio Investments (FPI) in Indian companies. The Indian government monitors investments that could lead to any level of influence over Indian firms, especially those with holdings above a certain percentage, which triggers additional layers of regulatory approval and monitoring.

There are plenty of EV manufacturers in China, the leading ones are BYD, SAIC-GM-Wuling (SGMW), NIO, XPeng Motors, GAC Aion, Gilly, Li Auto, BAIC Group (BJEV), Cherry and JAC Motors. Likewise, India, too, has a few EV manufacturers, most of them being in 2 and 3Wheeler sectors like Ola Electric. Ather Energy, TVS Motors, Bajaj Auto, TVS Motors and Piaggio.

In 4Wheeler, the major players are Tata Motors, Mahindra Electric and MG Motors, a subsidiary of China’s SAIC Motor while Olectra Greentech specializes in electric buses for public transportation that provide sustainable solutions for mass transit in cities. India has imposed a steep duty on the import of EVs; India is interested in the trade of Electric Vehicle Components and Technology Transfer.

Presently, lithium-ion battery technology and production are of utmost importance for India while other components of the supply chain, too could be helpful for the Indian EV industry. Further, knowledge sharing in EV technology would allow Indian companies to leverage Chinese advancements in EV production and assembly processes including technology advancement, cost reduction and promotion of domestic EV capabilities but it all depends on improvement of the relation between both countries.

India’s stance on Chinese investment is closely tied to the geopolitical situation. While trade between India and China continues, and Chinese products remain prominent in the Indian market, relaxation in investment policies and tariffs on Chinese goods are dependent on trust building between the two nations. India is being pulled by both blocks, the Russian and the American but Indian policy of neutrality is expected to continue.

Though Chinese firms like BYD, CAIC and Great Wall Motors are eager to establish production facilities or forming partnerships in India, the investment condition laid by the Indian government on Chinese investment is a road block. Likewise, Chinese condition of non-transfer of key technologies to India is a hindrance.

To start with, both the countries could explore establishing joint manufacturing hubs for EV parts, which would allow companies from both countries to benefit from India’s low production costs and China’s advanced technology. Such hubs could serve the South Asian market, making EVs more accessible regionally and promoting India as an EV manufacturing base.

Reduction of Cross-Border Trade Barriers and continuous dialogue is a must for improving Indo-China relations. This can result in faster movement of goods and reduced logistics costs, critical for the EV sector where parts and raw materials need to be transported efficiently. Faster routes through Himalayan region (infrastructure to be created) can reduce lead times, allowing Indian companies to adopt a just-in-time approach for EV parts, thereby reducing costs.

Lower costs would directly impact the final price of EVs in India, making them more competitive with traditional vehicles encouraging more consumers to make the switch. It will also help establish export of Indian EVs. Both India and China are highly committed and invested in the reduction of carbon emissions. Improved relations may lead to collaborative environmental policies that facilitate EV adoption.

These could include agreements on EV standards, infrastructure, and carbon credits, aligning both countries’ EV industries with global sustainability goals. An improved relationship can open doors for India to adopt Chinese best practices in EV infrastructure. This includes rapid deployment of charging stations and battery swapping stations, which China has successfully implemented in their urban centres.

Even with improved relations, both countries may remain cautious of becoming overly dependent on one another for critical components like EV batteries. India may continue to explore alternative partnerships to reduce dependence on China in case geopolitical tensions resurface. There could be concerns about technology transfer, especially regarding intellectual property and cybersecurity, given the sensitive nature of EV software.

Both governments may need to address these issues through protective policies to safeguard their national interests while promoting collaboration. Increased Chinese investment in the Indian EV sector could lead to job creation in manufacturing, R&D, and supply chain. By establishing EV manufacturing facilities in India, Chinese firms could contribute to developing a skilled workforce that benefits the Indian economy.

Partnerships between Indian and Chinese companies might bring skill development programs that train Indian workers in advanced EV manufacturing techniques. Further, India and China could explore joint export strategies for EVs to third-party markets, especially in Southeast Asia and Africa. New trade agreements may include clauses beneficial to EV export, which would allow Indian and Chinese companies to leverage each other’s resources and networks for exporting EVs to these regions.

Be that as it may, the Chinese proposals are vetted based on their impact on Indian industry, national security, and other strategic factors. Proposals involving sectors that impact national security or critical infrastructure also undergo additional scrutiny by agencies like the Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). In some cases, the Ministry of External Affairs is also involved to assess any geopolitical ramifications.

Due to these layers of scrutiny, the approval process for Chinese FDI often takes longer than for other countries. This extended timeline delays the entry of Chinese investments, which can affect both the business interests of Chinese investors and the capital flow into Indian industries. Further, there are caps in certain strategic or sensitive sectors for ensuring that foreign entities do not hold controlling stakes.

For Chinese FDI, the government may set additional restrictions on equity ownership levels, particularly in sectors deemed critical to national interests. Indian regulations now require more extensive disclosures regarding the beneficial ownership of Chinese entities investing in India. This is to ensure there is clarity on who ultimately controls or benefits from the investments, which helps the Indian government assess risks more accurately.

Chinese EV companies may take the benefit of Indian policies that encourage Chinese companies to invest through joint ventures or partnerships with Indian firms, which can facilitate knowledge transfer while ensuring Indian control over key strategic areas.

In sectors where Chinese EV/battery firms have advanced technologies, India should encourage technology transfer agreements for which the Chinese government will have to change their policy for technology transfer. These actions can allow Indian firms to benefit from Chinese expertise without relinquishing ownership or control, supporting India’s long-term economic interests. But this can happen only when trust is built between both the countries. Both the countries need to take steps forward to build a global EV ecosystem, thus, achieving their Paris commitment towards sustainability, thus, helping mankind at large.

(The author is Former CEO, Scooters India Limited, presently CEO, FORE Academy; Views are personal)